By NOEL MURPHY

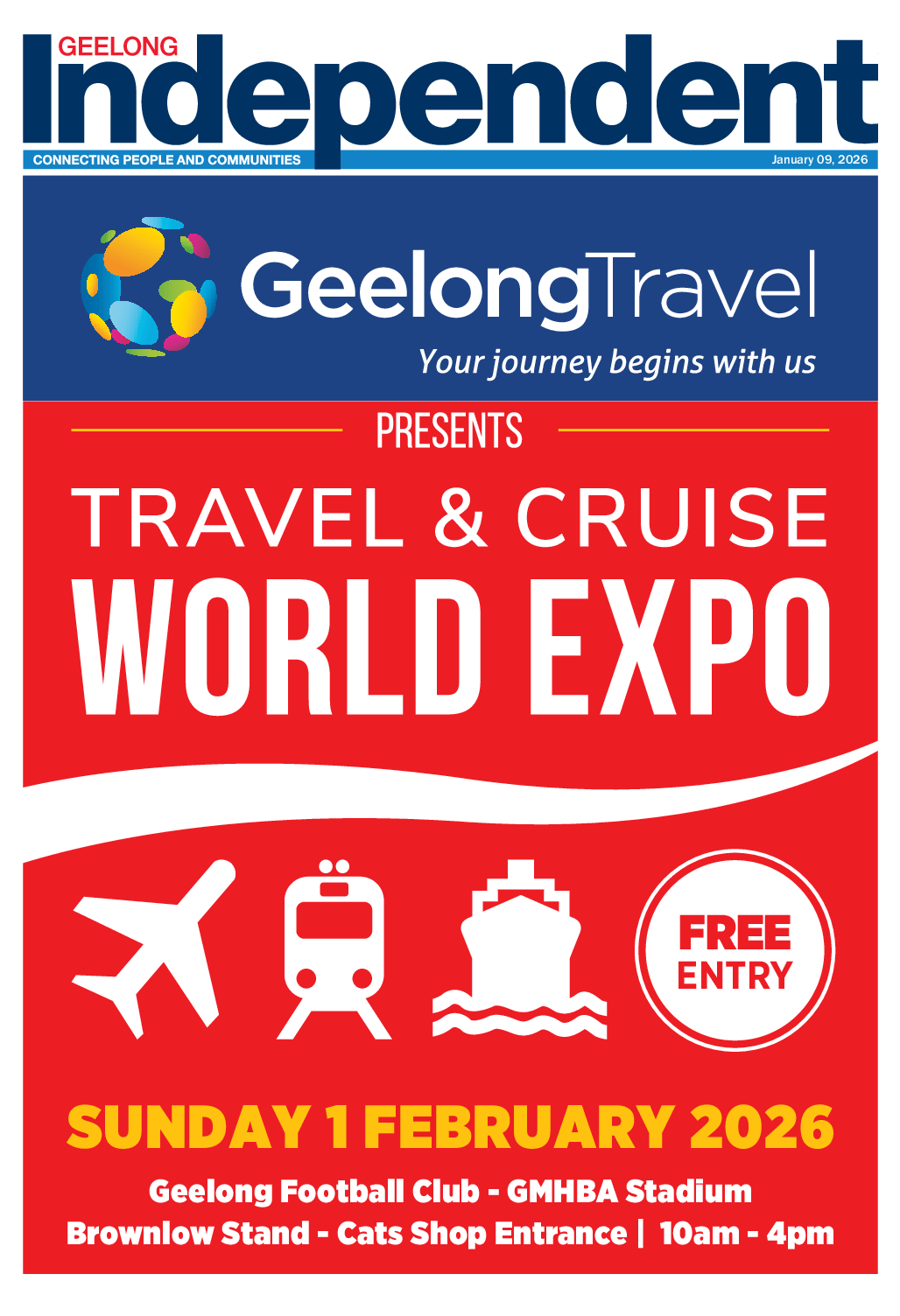

THE pink-capped, geodesic-styled dome rising over Johnstone Park speaks to a new heritage emerging from what was a reeking swamp in Geelong’s beginnings.

The stagnant pool, fed from a creek-bed along present-day Gordon Ave and cut off from its Corio Bay destination by earthworks on Gheringhap St, was to have been a public reservoir but swiftly became a dumping ground.

Animal carcasses polluted its waters and people even drowned there before it was drained and gardens planted across its reaches. Ferneries, flowers, trees, ornamental settings, even staircases and sunken formal garden beds sprang up in the park.

So, too, did architectural edifices around its borders: the classically-inspired town hall and war memorial, bluestone churches and banks, courts and police utilities, an imposing cantilevered ‘Irish pyramid’ and other concrete examples of brutalism such as an arts centre.

A new $45 million library-heritage centre occupying the six-storey dome, sharing space also with Geelong Gallery, speaks volumes to a heritage the city has struggled to properly recognise or accommodate in recent decades.

Geelong’s museum disappeared in the 1950s and local collections have been scattered across the region. The contents of the original have been scattered to the winds.

But the new heritage centre will act to change that lack of focus.

Geelong’s heritage is a rich one, geologically, culturally and historically. Its indigenous wealth is formidable, its palaeontological riches likewise, its white settlement and pioneering days replete with accounts of endeavour and achievement.

Geelong was built amid a clash of cultures, white and indigenous, and an immigration frenzy – an Antipodean diaspora – fuelled by gold, wool and the prospect of a better life, broader opportunities, in a new, developing land.

It was a wild and rambunctious place. Its first police boss, Foster Fyans, came from no less than the terrifying convict concentration camp, Norfolk Island.

People could become rich in the new southern continent and, not surprisingly, they arrived in droves. Timber shacks and suburbs sprang up across the settlment then known as Jillong, starting to the south beside the Barwon River and to the north along Corio St beside the shore of Corio Bay.

It was a rough, rudimentary village; its muddy roads rutted by hooves and wooden wheels, its water provided by cart and its bustling commerce centre not like today’s Sovereign Hill. But light, gas, electricity and manufacturing evolved, enterprises became more sophisticated as its people marched off to wars and as new waves of immigration brought others flocking to the once tiny agrarian outpost on the edge of the world.

Dams and water storages were built, running water developed. Stormwater drains were installed beneath Johnstone Park as it became a centre of civic elegance and focal point for not just Geelong’s populace but visitors from afar.

The new heritage centre will host 100,000 books along with conference and functions areas, indoor-outdoor kids space, interactive sculpture, gallery, high-speed wi-fi and a five-star green-energy rating.

Some 400 prefabricated glass-reinforced concrete tiles make up its semi-spherical rooftop – a design testimony to a classical style lent to major public institutions the world over. Even so, it’s markedly different from its adjoining classical structures, let alone anything Port Phillip superintendent Charles Latrobe might have envisaged when his pool was set up in the 1840s.

It’s solar panelling can even be seen hidden on top of the park’s war memorial.