The Independent is looking back at our best feature stories of last year, and this is one of them.

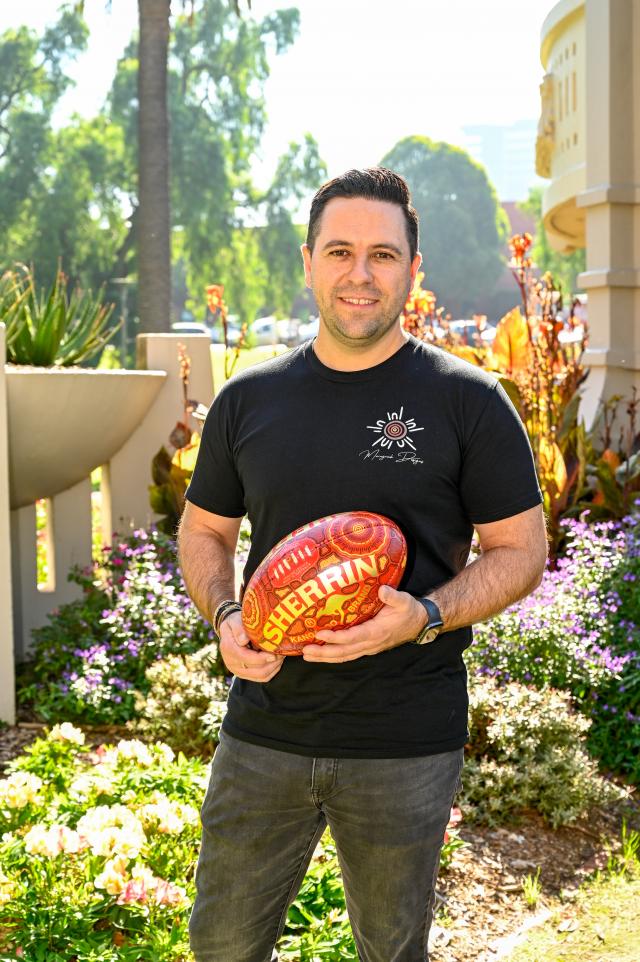

Proud Dja Dja Wurrung man Ricky Kildea is well known for his visual art designs, which have featured on Formula 1 driver Valtteri Bottas’ helmets and footballs for the AFL’s Sir Doug Nicholls round. However, as he explained to Matt Hewson, it is his passion for the work he does in and for his community that drives him.

Geelong’s Ricky Kildea remembers having a love for both football and community from an early age, inspired by his father since he was a boy growing up in Victoria’s southwest.

Born in Warrnambool, Ricky spent most of his younger years living on the family property at Stoneyford, near Camperdown.

“We grew up off-country in terms of where our heritage is from, which goes back to Dja Dja Wurrung country, up toward Bendigo way,” Ricky said.

“We didn’t grow up there, so we were a little disconnected, but we were always involved in Aboriginal community events and stuff.

“I grew up playing in Aboriginal footy carnivals when I was a young fella. Dad used to coach local footy teams down in southwest Victoria and he had a pretty incredible record, something like seven premierships from nine grand finals.

“He loved coaching footy and I loved becoming a part of that. So on the footy side of things he was a really big influence for me, but I think later on it was seeing how much he gave back to community. He poured his heart and soul into Aboriginal education.”

Ricky’s dad, Terry Kildea, was born in Mooroopna on Yorta Yorta country and was raised by his grandmother of the Dja Dja Wurrung people in Central Victoria.

Terry was an educator and leader, and was heavily involved with taking the Indigenous Education Centre at Kangan Institute in Broadmeadows from a small portable building into a purpose-built Aboriginal-designed centre.

“They had some incredible numbers; the highest number of educational hours delivered for Aboriginal students in the state, they won awards and everything,” Ricky said.

“Seeing how much of an impact he could have on people and community, that was something that really inspired me.

Ricky had gone through the Aboriginal Football Development Program with Eddie Betts and then became a qualified personal trainer based in South Yarra.

“I was both running the business and working in it, which was really good,” he said.

“I did it for about four or five years, and then I started thinking about where I was. I really enjoyed what I did but I was a bit disconnected from Aboriginal community.”

With that passion for community driving him on, Ricky began a career transition, still maintaining his personal training business but also taking on part-time work at a health service in Broadmeadows.

Then, in 2010 Ricky took the plunge and applied for a job working in prisons as part of a Deakin program to provide student support for indigenous students in custody.

“A lot of my friends said I was crazy,” Ricky said.

“‘What are you doing? You’re training people who have got a bit of money, in South Yarra, Chapel Street, and you’re going to do distance education support for Aboriginal inmates at a maximum security prison?’

“But I’d seen my dad bring in people who had nothing, but he had this ability to find something in people they didn’t feel like they had. Seeing him get them to a stage where they could change their whole life, that’s what I wanted to do.

“The idea was to have Aboriginal inmates get a qualification or degree while they were inside, which is pretty tough.

“I mean, getting a uni degree at the best of times is hard, let alone being in custody. So it was really challenging, but it was different and I really enjoyed it.”

By 2016, Ricky had transitioned into managing student support at Deakin’s Koorie Institute.

Then he and his family’s life changed forever when his father Terry died in an accident in December that year.

“It was pretty tough after Dad died; it was a shock for everybody,” Ricky said.

In the years preceding his passing, Terry had founded Wan-Yaari Aboriginal Consultancy Services, which he had intended to pass on as a family business.

“He’d set up Wan-Yaari prior to that; he’d retired two or three times but always ended up back working,” Ricky said.

“So my brother-in-law and myself sat down and said, well, we’ll continue Dad’s legacy and jump in full-time; it’s full steam ahead or not at all.

“It was a tough time. I’d lost my role model, my dad, and I was starting a business from scratch, trying to grieve and get the business going at the same time.

“But as tough as it was, the really key drive was that it was in Dad’s memory. It was like, it didn’t matter how tough it was, it meant something so you kept on doing it.”

That drive has helped Ricky bring Wan-Yaari to where it is today, running multiple programs in consultation, education, employment support and custody-to-employment pathways.

“Wan-Yaari means to listen, learn and understand, so we have that educational piece behind a lot of the stuff that we do,” Ricky said.

“We do consulting work, a lot of community programs, but at the moment our prison-to-work program is the main program.

“It’s tough but we’re getting some good outcomes, so it’s all worthwhile. One of our trainees from last year won (Victorian) Indigenous Student of the Year and just missed out on overall Trainee of the Year.

“He finished his traineeship and now he’s gone on to be a supervisor, so he’s killing it.”

The role of director and lead consultant at Wan-Yaari has been demanding for Ricky, who now has a family of his own.

Through the COVID-19 pandemic he felt the need to find a personal form of expression and relaxation.

“I found I was taking work home most nights, which most people do when you’re running a business,” he said.

“It was consuming a lot of my time. As soon as the kids were in bed I’d switch back on and do work until 11 o’clock at night.

“So painting became a way for me to say, alright, maybe I’ll just leave the work stuff for the next day.

“It’s something where I can just switch off and look after my mental health and wellbeing a little bit better.”

Before he knew it, Ricky’s Instagram was drawing lots of interest, and he found himself painting a football for former Melbourne player Neville Jetta.

His football designs have featured in Sir Doug Nicholls rounds as gift exchanges and awards for best on ground, and before he knew it a series of connections led to Ricky designing two helmets for Finnish Formula 1 driver Valtteri Bottas for the 2023 Australian Grand Prix.

“He wanted two helmets done, one for him to keep and the other to be used in the race and then auctioned off,” he said.

“It sold for just under $50,000, which is pretty crazy. We wanted to give back, so they chose a charity and I chose one.

“They chose Save the Children, which ironically ended up going toward a kindergarten in Mooroopna, where my dad was born, so that’s a nice little connection.

“I wanted to choose one that I knew would have a grassroots-level impact, so the other one is the Koorie Academy of Basketball. They’re going to hold a basketball and cultural clinic down here in Geelong.

“I’m hoping we can have Valtteri come and attend as well, but he’s a pretty hard man to schedule time with, so we’ll see how it goes.”

While Ricky enjoys seeing his artwork out in the public eye, it’s something he wants to keep as a personal process rather than work.

“Painting doesn’t start until nine o’clock after the kids are in bed, and I paint as long as I can keep my eyes open,” he said.

“When opportunities come up, like the helmets, I take it, but I still want to have it as an outlet where I can just switch off.

“The really important stuff happens between nine and five.”