A time-worn gravestone in Eastern Geelong Cemetery reveals the tale of a farmer “cruelly murdered at midnight” – a crime that remains unsolved after 137 years.

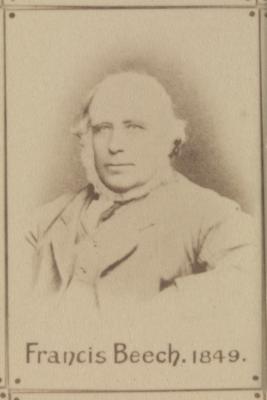

Geelong historian Doctor Peter Mansfield steps back in time to investigate the murder of Francis Beech, and vindication of his “beloved” widowed wife, Jane.

On January 21, 1884, Francis Beech was shot dead by an intruder who broke into his farmhouse at Pettavel.

Beech was a prosperous cattle dealer, who lived with wife Jane.

They employed a maid named Amelia Clark and an apprentice butcher named Frank Howarth, with all four living in the sprawling farmhouse.

About midnight, Mr Beech heard breaking glass and confronted an intruder, who fired six bullets.

Four struck and killed Mr Beech, one bullet hit Mrs Beech in the arm and the other embedded itself into the wall.

The intruder fled and Mrs Beech’s screams attracted staff before she fled to her maid’s room, and fainted.

The young apprentice butcher bravely rushed out into the night to seek help from neighbours.

Police officers and a doctor arrived on the scene before dawn and a coronial inquest took place that afternoon.

The police magistrate took evidence from Mrs Beech, Miss Clark, Mr Howarth and the doctor.

The inquest found that no money had been stolen and no apparent motive for the violence. The official finding was that Francis Beech had been murdered by an “unknown person”.

The police brought three Aboriginal trackers from Melbourne by train and they followed the escape route before losing the trail due to heavy rain.

But police were confident of an early arrest, because the intruder had left footprints and dropped a distinctive cigar holder on the road. The murderer had also thrown the revolver into a shallow dam.

Despite their confidence, the officers could not find the culprit and the government offered a £200 reward (roughly $46,000 Australian today), with Mrs Beech adding another £50.

On January 24, 1884, Mr Beech was interred at Geelong Eastern Cemetery in a huge funeral.

More than 50 horse-drawn carriages carried in mourners, followed by another 50 men on horseback.

Meanwhile, police continued their colony-wide search for the murderer.

They discovered the murder weapon had been sold by a registered gunsmith in Melbourne but the vendor had no records of the sale.

The distinctive cigar holder was typical of a style adopted by prisoners at Pentridge Gaol.

Three months later, police announced that the prime suspect was William Bourke.

The Police Gazette on March 19 instructed officers to be on the lookout for “William Bourke, alias Irwin, alias Captain Donovan – an escaped lunatic”.

Police arrested Bourke at Mortlake and he faced the Geelong court on April 8. In spite of repeated reference to the fact that Bourke was insane, he was charged with murder and the trial commenced.

Prosecutors presented evidence that Bourke was a “compulsive walker” known to travel 80 kilometres per day and often wore filthy, bloodstained clothes for a week at a time.

His alibi was that, on the night of the Beech murder, he was on a crime spree in Melbourne and wearing shoes that he had stolen that night.

On the second day of the trial, the court ruled the accused was insane and could not be found guilty of murder. He was then returned to an asylum in Melbourne.

Fifteen months later, in April 1885, Geelong residents were shocked to read that police had arrested Mrs Beech and their butcher Mr Howarth for the murder of her late husband.

Police had conducted two pre-dawn raids and taken both suspects to the Geelong prison. Bail was denied and they spent a week in prison awaiting trial.

At the time of their arrest, Mrs Beech was living with relatives in Geelong. Howarth was a newly-married man living in Moolap.

Superintendent Toohey gave the press “exclusive” information, which turned out to be more fanciful than factual.

When the accused came to court it was found that police had relied on gossip supplied by the former maid, Miss Amelia Clark, and had embellished other evidence.

After a two-day trial, a panel of eight justices of the peace threw out all the charges against Mrs Beech and Mr Howarth.

The crowded courtroom erupted with applause and Mrs Beech fell to her knees praising Jesus for deliverance, and was so emotional she had to be carried from the court.

The press labelled the trial a fiasco and said that “Toohey may have been a good policeman but was a poor detective”.

In June 1885, the accused took legal action against the police force.

But the police and government closed ranks and all charges of wrongful arrest and malicious prosecution were dismissed.

Superintendent Toohey escaped with little more than a reprimand.

The murder remained unsolved. Every few years the case was discussed in the colonial press, but to this day no one has discovered who shot dead Francis Beech.

Mrs Beech died in 1926 at age 95 after spending more than 40 years as a widow.

She was interred at Geelong Eastern Cemetery with her husband, “cruelly murdered at midnight on the 22nd of January in his 65th year”.