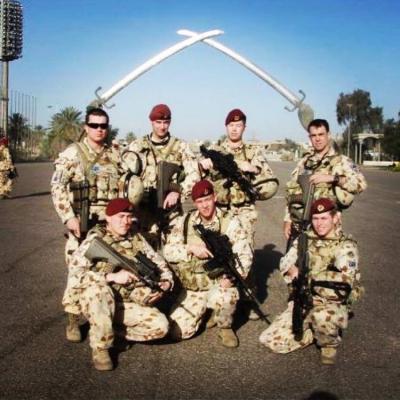

With Anzac Day marches returning to Geelong on Sunday, veteran Chris Leach speaks to Luke Voogt about his service in Iraq, Timor Leste and the Solomon Islands.

Within 72 hours Chris Leach went from being mortared and peppered with machine gun fire in Baghdad, to sinking schooners in a Sydney pub.

“There was no fanfare – just a phone call to mum and dad to say I’m home,” remembered the 36-year-old veteran, now working as a plumber in Geelong.

“Our CSM [company sergeant major] and RSM [regimental sergeant major] met us at the airport and we got on a bus – that was it.”

The deployment was part of a four-year army career that began in 2005 when Chris joined at age 19.

His grandmother Joy served in Signals Corp during World War II, while his great-great-grandfather and great-great-uncle on her side both served in World War I.

“She was the first person in her extended family to get her driver’s licence, and she got it in World War II,” he said.

His grandfather Alan, who married Joy after the war, joined at 16 and was one of Australia’s youngest prisoners of war (POWs) when the Germans captured him in Greece.

But pragmatism, rather than his family’s military heritage, drove him to enlist.

After leaving school in year 10 and working on cattle stations in the Northern Territory, he was struggling to find work as a shearer back home in Mansfield.

“I needed a job,” he said.

“[My parents] were pretty happy to move me along, I think.”

His fitness and high aptitude scores allowed him to join as a direct-entry commando, and he had just days to prepare when a place came up.

“I rang them on Thursday and I had to leave on Monday,” he said.

After basic training at Kapooka he completed infantry training, which was “twice as hard as Kapooka”, and an advanced infantry course that was “twice as hard” again.

There he lugged 45 kilograms of equipment 45 kilometres in less than a day, and another time was treated like a POW before being led underground blindfolded into a World War II bunker complex in Newcastle.

“You had to cross your legs in an awkward position and lean forward so it’s really uncomfortable for 20 minutes,” he said.

“They would ask us questions and we could only let them know our name, rank, PM Keys [serial number] and date of birth.”

Holding hands to stay together, the trainees felt their way out of perhaps a kilometre of “pitch black” tunnel.

“I was pretty calm – you know your mates were there with you,” Chris said.

But a knee injury he sustained while packing up left him unable to complete a final physical ‘barrier’ test.

So he accepted the army’s offer to join 3 RAR instead, then an airborne (parachute) infantry battalion.

He was “naïve and confident” flying up in the back of a Hercules for the first of 13 jumps during training in Nowra, NSW.

“I wasn’t prepared for the force of jumping out – being upside down and flung around,” he said.

“I had my eyes closed. It took a good five seconds for the chute to open.”

The trainees then progressed to jumping with weapons and full kit, including a large backpack.

“After that it wasn’t much fun. There were guys throwing up in the plane,” he said.

Soon after he was deployed to “the hotter than hell” Solomon Islands as riots flared and locals burned down Chinatown in Honiara.

“The hottest place I’ve been in my life,” he said.

“We did patrols through the jungle and came across Japanese machine gun posts, US landing craft.”

Many of the locals had collected other World War II relics, including helmets and even skulls, he added.

While there to prevent violence, Chris empathised with the locals, particularly after gathering “horrendous” intelligence from them.

“I was conflicted,” he said.

“The Australian government sent us over there to pacify the locals protesting about the Chinese taking over their county.

“[The locals said] Chinese guys would buy local girls, take them on the fishing boats with them and later throw them overboard.

“So that was eye-opening as a 19-year-old from Mansfield. I’d never been overseas.”

He fondly remembered giving water and lollies from his ration pack to local kids.

“A positive was meeting the locals and the kids were happy to see us,” he said.

“We went to one very remote village and they sung to us, which was really cool. I’d like to go back there.”

Months later Chris was flying over palm trees, buildings and smoke in Baghdad in a Chinook helicopter as tracer rounds shot past in the middle of the night.

“That will be something I never forget,” he said.

Later, he and his comrades were aboard Australian Light Armoured Vehicles (ASLAVs) speeding through peak-hour traffic and down Baghdad Airport Road on supply runs.

“It was the most dangerous road in the world at that point,” he said.

“On a daily basis there were 2500 incidents in our area of operation.”

Designated Route Irish, the highway linked Baghdad International Airport to the fortified green zone, including the Australian Embassy where Chris was part of security detachment.

The constant threat of ambushes, mortars, rockets and improved explosive devices (IEDs) was a rush, he said.

“I loved it. It’s like training for football then getting a game, that’s the best way to describe it.”

With a top speed of 100km/h, the armoured mobility of their ASLAVs was key to survival, Chris explained.

“As soon as we got into any danger we would bug out – we never stopped,” he said.

On one night supply run insurgents set three cars on fire to block the highway.

Chris’s convoy arrived as Iraqi soldiers engaged the insurgents, and the lead ASLAV “pumped” 25 millimetre cannon rounds into enemy machine gun positions before punching through the car wrecks and continuing on.

“[The insurgents] had 50 [calibre] machine guns set up in the houses,” he said.

“We were getting peppered – you could hear the bullets smashing the side of the ASLAV.

“All your senses are firing on all cylinders – a massive rush.”

Back at a US base, the soldiers spotted bullet holes in sandbags they had placed around the hatch of the ASLAV for extra protection.

“It would have been 50mm below where their heads would have been,” Chris said.

Chris also remembered a mortar shell exploding in the doorway of a mess hall where they were eating, killing several American soldiers.

“We were instantly under the table,” he said.

Chaos ensured as American soldiers streamed through the ruined doorway to get to bunkers.

“There were people jumping tables – it was mental – the mess was empty in about three seconds,” he said.

“The only ones left in there were the Australians and the Poms.

“It was too panicked, we just had to wait until it settled.”

Chris’s section stayed knowing the insurgents would not likely land another accurate shot, Chris explained.

The US Military had airborne detection systems to pinpoint the origin of mortar attacks, before their battery of howitzers bombarded the location, he said.

“They could zero in on exactly where the shell came from.

“Two minutes later, in the distance, you would see a big boom. It was unbelievable how efficient they were.

“That’s why I wasn’t concerned at the time – I thought, ‘that was their last shot’.”

Often American soldiers spoke to them about the welcome home parades waiting for them.

“We couldn’t wait to get home too – we would be hailed as heroes,” he said.

Instead, Chris and his comrades made do with several schooners at the Criterion in Sydney.

He was soon diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and self-medicated.

“I had massive issues sleeping – I couldn’t get to sleep for months,” he said.

“There were always shots being fired 24/7 in Baghdad so I was always wound up. There was no way I ready to be in civilised society.”

After four weeks of leave, Chris joined a security detachment for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meetings before another five-month deployment to Timor Leste, which he described as “boring” compared to Iraq.

But as a combat first aider, he, medics and an army doctor got choppered into remote villages to help locals.

“That was kind of cool,” he said.

He left the army in 2009 and in 2011 moved to Buckley, joining three army mates who had moved to the Geelong area.

He still bears the knee injury that barred him from commandos, along with back issues.

“I’m 36 now and sometimes I struggle to put my boots,” he said.

He now runs Clearwater Plumbing in Newtown and has hired a Geelong born-and-bred veteran to work for him.

“I’m always chasing them,” he said.

“I know they’re very mission-orientated. They do a good job and reap the rewards from it.”

After COVID-19 cancelled Anzac Day commemorations in 2020, Chris plans to march in central Geelong this Sunday.

He looked forward to commemorating the day with his two sons, aged six and eight, and perhaps a third, with his partner expecting.

For Chris Anzac Day is about remembering mates killed in combat or those who took their lives after returning home.

“It’s really a day to connect with all the other vets so they don’t feel alone,” he said.

For help phone Open Arms on 1800 011 046.