As Australia and the world struggle with COVID-19 and vaccine shortages in 2021, many would be surprised to learn Geelong doctors faced similar fears, anti-vaxxers and supply problems almost 170 years ago.

Geelong historian Doctor Peter Mansfield journeys back to 1852, when the infamous ‘Plague Ship’, The Triconderoga, arrived upon our shores.

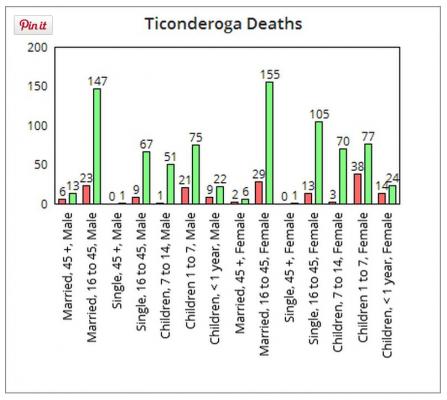

Just a year after Victoria became a colony, the infamous ‘Plague Ship’, The Triconderoga, arrived at Port Phillip Bay from the US with hundreds of passengers suffering typhus and scarlet fever.

A temporary quarantine station was established, and the immediate problem was contained, but colonists were so alarmed that they forced the government to take control.

The Victorian parliament adopted the Compulsory Vaccination Bill in 1854. The rules were simple.

All babies had to be vaccinated within three months of birth, children under three had to be vaccinated within the next six months, and all other children and adults had to be vaccinated as soon as possible.

The vaccination of yesteryear was a rough old system – far less precise and safe than inoculation today.

Rather than using dead or weakened viruses, or components such as proteins, to trigger an immune response, doctors would smear an infection on a person in hope they would become immune.

One treatment, developed in England, involved using cowpox to immunise patients against the similar disease of smallpox.

Cowpox caused mild symptoms in humans, compared to the highly-contagious and often deadly smallpox.

With most inoculations, doctors would cut a little slice in shoulder and infect it with a vaccine, often in imprecise quantities, and bind the wound for a few weeks before inoculating the patient second time.

Many would not come back for the second inoculation, or could find no doctor available, especially in rural areas.

Doctors were paid two shillings, about $30, per vaccination.

But colonists remained terrified of smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid. They were convinced that new arrivals and gold-seekers would infect them and kill their children.

Typhoid was so common that it was seldom discussed in press reports. Luckily, it was not as fatal as smallpox.

Another quarantine station was established at ‘The Heads’, meaning Queenscliff, and every ship’s captain was required to inform the authorities of any sickness among passengers and crew.

However it took 10 years for the reporting phase to be perfected. Meanwhile the forced isolation of the sick was described as “harrowing” for all concerned.

A standard remedy was fumigating or burning a victim’s possessions, so surviving a contagious disease often resulted in years of poverty.

Geelong’s first public vaccinators, including John Findlay and Dr James Edmonstone, were appointed in 1854 when Geelong’s population was about 8000.

The decision to vaccinate every child and then, every adult, increased community confidence, but the practical application of the act was not without its difficulties.

Many parents opposed the vaccination of their children and faced heavy fines.

The penalty could be as high as one week’s pay, but it seems that magistrates often waived fines.

The medical profession argued about the number of doses of the vaccine required to ensure the safety of individuals.

These arguments added to community unrest and the government was forced to place advertisements in the press re-assuring residents that officials knew best.

Public hospitals were banned from admitting patients suffering contagious or infectious diseases and any patient hoping to be treated by a hospital doctor was “sent home with advice”.

That advice included burning the patient’s bedding and clothing. Not surprisingly, the rate of self-reporting was not high.

Dr Mingay Syder, a Geelong GP, wrote numerous letters to the editor demanding that Geelong hospital establish a fever ward for the poor and destitute.

But in his own practice, Dr Syder said he “excluded those who have rendered themselves destitute by intemperance, debauchery and indolence”.

Many doctors opposed compulsory re-vaccination and the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination Society formed branches throughout Victoria.

Doctors opposed the accreditation of “unqualified and foreign doctors”, while the medical profession also opposed the appointment of non-medical vaccinators, such as school teachers.

There was a severe shortage of trained doctors in country areas. Distance was always a problem.

The medical vaccinator for Ceres, Grovedale and Connewarre had his practice in Malop Street, Geelong, and refused to make house calls.

The residents of Lorne were more fortunate. They negotiated to pay a doctor to visit their township and vaccinate every child in one day.

Constant arguments erupted about the effectiveness of the cowpox vaccine and the government’s ability to supply sufficient quantities of the serum.

In 1884, the Geelong Town Council leased an isolated farm at Moolap on the understanding that it would commandeer the building as a quarantine station in case of an emergency.

Thirty years after the adoption of Victoria’s Compulsory Vaccination Act, the arguments about vaccinating all residents were over and the government and medical profession were well-organised to protect the community.

Today governments are again battling to immunise Australia and the world, this time against COVID-19, despite vaccines being much safer, more precise and far more effective than in the 19th Century.

But even with the more stringent requirements for vaccines today, medical professionals still face the public fears, anti-vax groups and shortages of their forebears dealt with almost 170 years ago.