Paul Tinkler was part of a Deakin University team which recently scanned the seafloor of the Apollo Marine Park to learn more about what lies beneath the waves. He spoke with Luke Voogt about what the marine mapping exercise uncovered.

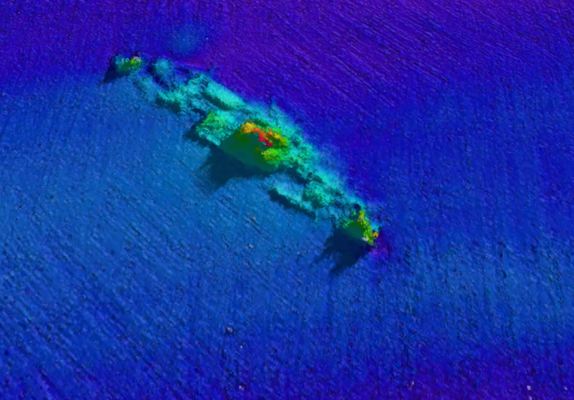

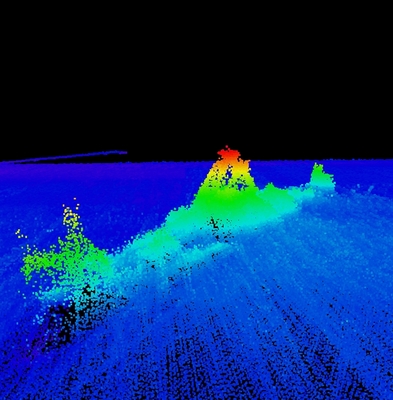

An ancient river valley, millennia-old habitats and the first American ship sunk in World War II all appeared in a recent seafloor mapping of Apollo Marine Park.

Paul Tinkler, who grew up in Manifold Heights, and his team travelled 884 kilometres, mapping more 119 square kilometres of the marine park, off Cape Otway, in eight days.

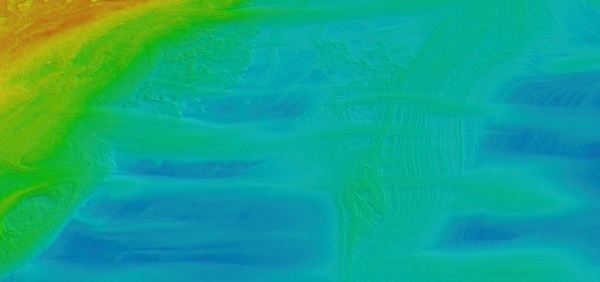

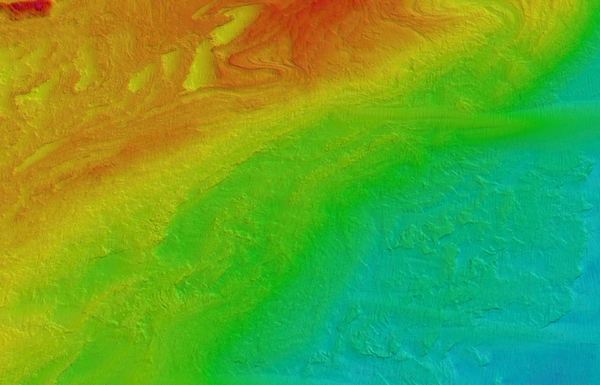

Their mapping, the most comprehensive of the area yet, revealed an 18,000-year-old river valley from the last ice age, when sea levels were lower.

“You could walk to Tasmania if you go back far enough in time,” said Paul, Deakin University’s senior marine technical officer.

“We were suspicious that something like that would exist but no one had mapped it before.”

The team used a combination of a global positioning system (GPS), motion sensors and multi-beam sonar to map the area, 50-metres to 100-metres deep, in greater detail than ever, Paul said.

“[The sonar] sends out something like a million beams a minute,” he said.

“It’s like a normal person’s fish finder in their boat, but on steroids.

“A fish-finder gives you a 2D map, whereas a multi-beam sonar is giving you a 3D version that is super detailed and super accurate.”

The state-of-the-art sonar is attached to a large arm on the researchers’ vessel, the MV Yolla, allowing them to lower it “very precisely”, Paul said.

The GPS and motion detectors take away “noise” in the data caused by waves and the movement of the boat, he said.

“[The GPS] can pinpoint our position to something ridiculous – I think five centimetres.”

Paul said the setup was unique for a boat the Yolla’s size and was normally mounted on a larger vessel.

“Larger ships can’t go that shallow,” he said.

“We can drive [the boat] down the highway and get it in where and when we need it.

“But the compromise is it can’t handle the same conditions as a larger vessel.

“The general rule of thumb is that gear can probably outlast the driver – it can still be working when the people start to struggle.”

Despite monitoring the weather closely, at times the team found themselves in waves five metres high, from crest to trough.

“We had a few days where we got thrown around quite a bit and days where we had to decide, ‘we’re not going to work today’,” Paul said.

“If you’ve got southwest swell meeting winds from an easterly direction, it gets pretty ugly.”

The researchers mapped about 10 per cent of the marine park, revealing fine-scale seabed features, reefs and ancient shorelines and rivers.

“To map the whole park would take a long time,” Paul said.

“So you target what looks like the most complex seafloor based on hydrographic charts.

“Sometimes it can feel a bit like mowing the lawn. You’re painting lines on the seafloor with the sonar unit and you’re then basically filling [the gaps between] in.”

Other researchers could study the shape of seafloor formations to determine land features from thousands of years ago, Paul said.

“It’s usually above my paygrade,’ he laughed.

But more importantly for Parks Australia, the data revealed a complex seabed of deep reefs that have sustained fish and other fauna for millennia.

“Potentially the next step is to find out what’s there – what’s living on those features,” Paul said.

“That’s the sort of work that we hope the mapping might lead to.”

The marine park is hotspot for biodiversity, including habitats supporting deep water corals, fish and commercially-important rock lobster, according to Deakin.

Researchers could use baited remote underwater video stations, which attract fish, to film the rarely-seen marine communities, Paul said.

“It’s about not only providing us the knowledge to get to know of the habitat but it gives Parks Australia the ability to manage that into the future.”

The project is the latest chapter of the 44-year-old research diver’s career, which began studying aquatic science at university.

Following uni, he worked in aquaculture before taking a year off to travel Europe and South America with, of course, some scuba diving thrown in.

“Some of the best diving I did was in the Red Sea,” he said.

When he returned to Australia at age 28, he reunited with teenage girlfriend Bronwyn and the two married.

They met at Manifold Heights Primary School, where Paul’s dad Brendan was the headmaster, and dated for three years beginning when Paul was 18, he said.

The couple would again travel Europe and Africa for a year, with Paul diving Lake Malawi, before he got a job at the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Perth.

In his seven years there he dived with whale sharks, humpback whales and reef sharks in “epic locations” including shipwrecks, Ningaloo Reef and Rowley Shoals.

“They seem inquisitive and at peace,” Paul said.

“They make you feel a little bit insignificant in the grand scheme of things.”

He finds diving mesmerising.

“It’s dead calm and crystal clear – I imagine that’s what an astronaut feels like in space – just drifting and feeling captivated by what’s around you,” he said.

“When those enormous things move past in the water but you can’t hear them – all you can do is see them right in front of you – it’s something to behold.”