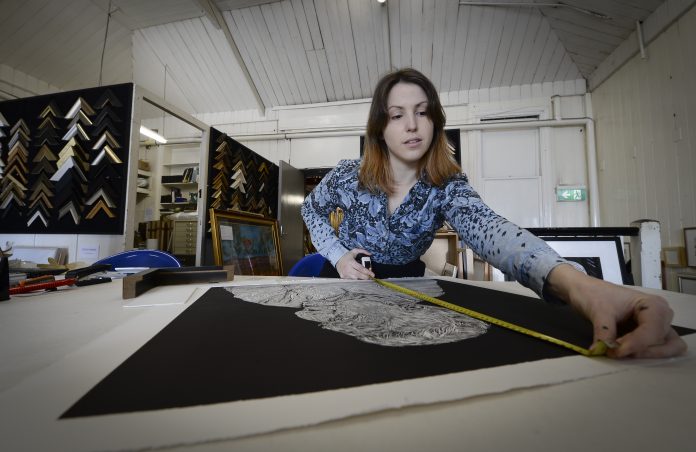

Geelong artist Keren Zorn is carving out her place in the arts with unique linocuts of furrowed faces. NOEL MURPHY steps into her studio …

FEW things in this world are more inscrutable than the human face. A smile can be something altogether different to what it seems, a basilisk stare might be a look of concern, a grimace … well, maybe just that.

Which makes them a veritable trove of material and inspiration for the artist. If expression is what the artist seeks to achieve, there’s little better than the human visage for expression by the artist, and for expression within the subject too.

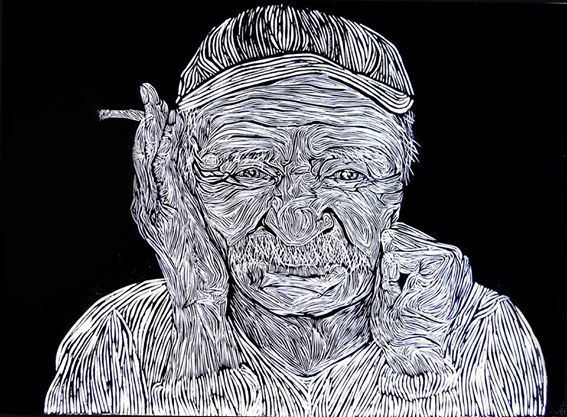

But Geelong artist Keren Zorn kind of confounds the norm by ensuring her artistic expressions remain deadpan. Her faces, and what lies behind them, don’t give much away. It’s up to the viewer to make their own mind up about what might be behind the face.

Imagination, questions, gut feelings, whatever the emotion her faces might evoke, they’re a viewer response. That’s why she won’t even name her subjects; they’re simply Man 1, Man 2 and so on.

It’s art. In the eye of the beholder.

Well, most of it. For Zorn, her art, her faces, are a life-time fascination in the five kilos of bone, skin, muscle, tissue and grey matter sitting on the human shoulders.

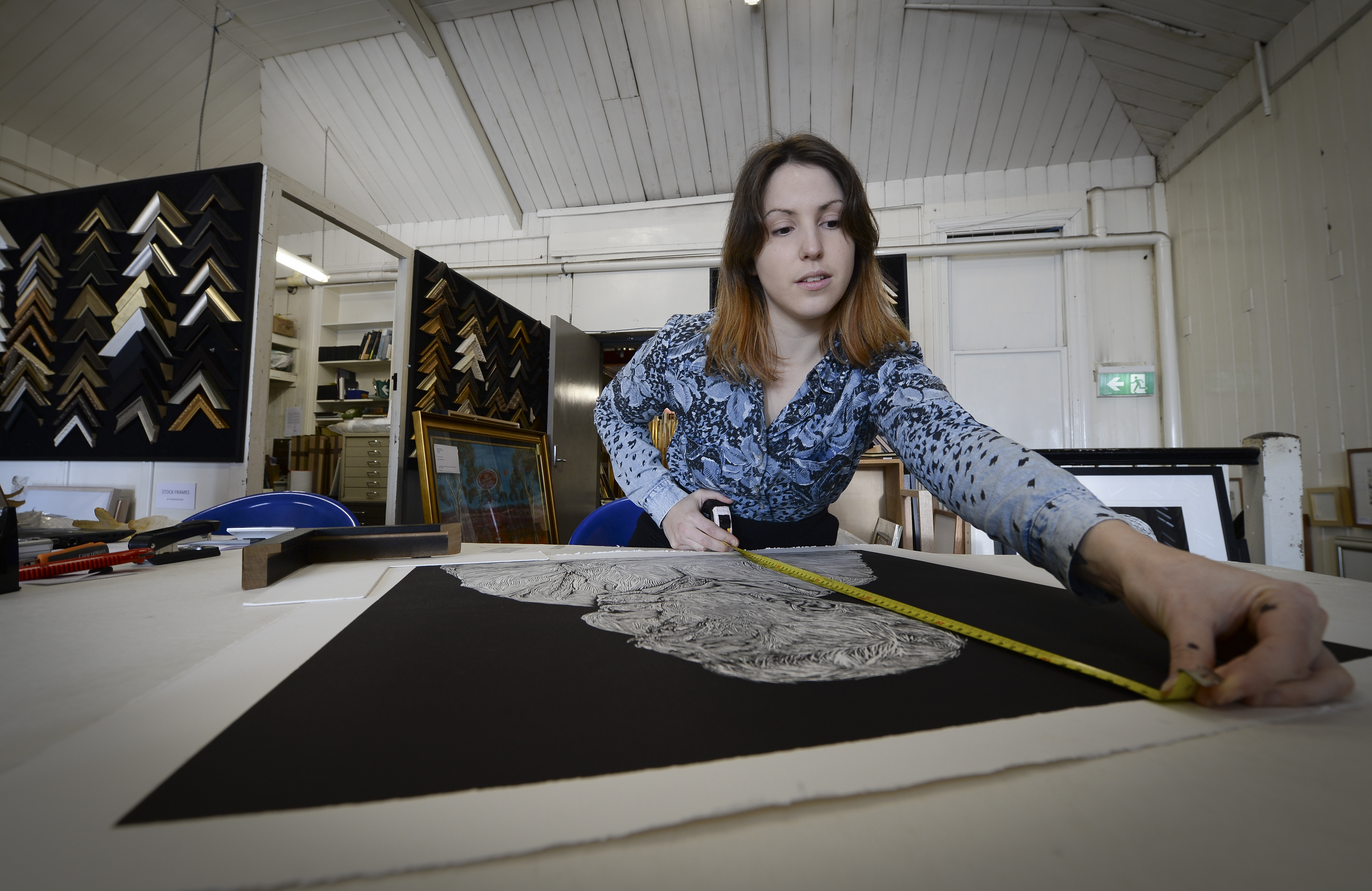

Zygomatics, parietals, maxillas and mandibles, occipitals, sphenoids – they’re all grist to the mill in her world of sketch, cut, ink and press. But what started in her younger days as a subject of oil paintings has evolved into a distinctive linocut pursuit.

Anonymity of the subject is critical. Zorn shies away from celebrities, so that her art might be viewed through its purest physiological, artistic prism.

“Really, expression doesn’t have to be complicated,” she says.

“I try to keep it simple. There’s nothing in the work’s title so it’s all in the eyes of the viewer.”

But there’s a lot to think about, she stresses.

“I’ve always gone for faces – and not necessarily faces with a lot of emotions.

“I started painting with oil, I’ve always liked texture a lot, and in high school I was always doing portraits so it’s something I’ve fallen into naturally.”

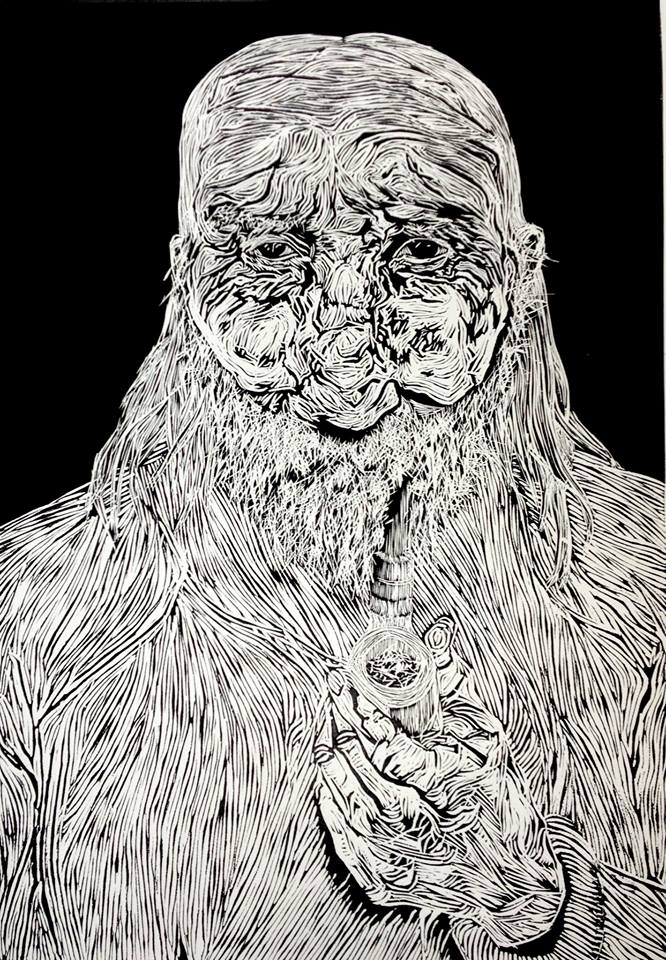

Texture now takes the form of distinctive cuts and scrapes, not unlike a surveyor’s topographical map in some regards, all amassed in a negative that’s then inked and pressed for the end result. Linocuts are art in reverse.

It’s a painstaking craft and one where Zorn says everything must be perfectly laid out. No room for error. But unlike many other artists, she doesn’t start with a rough orbital sketch of the head to provide a basic drafting roadmap.

Rather, she simply starts with the nose, the face’s central feature; sketching it in detail and diligently working her way outwards – eyes, mouth, ears – checking perspective, balance, distance between features as she goes. It works fine.

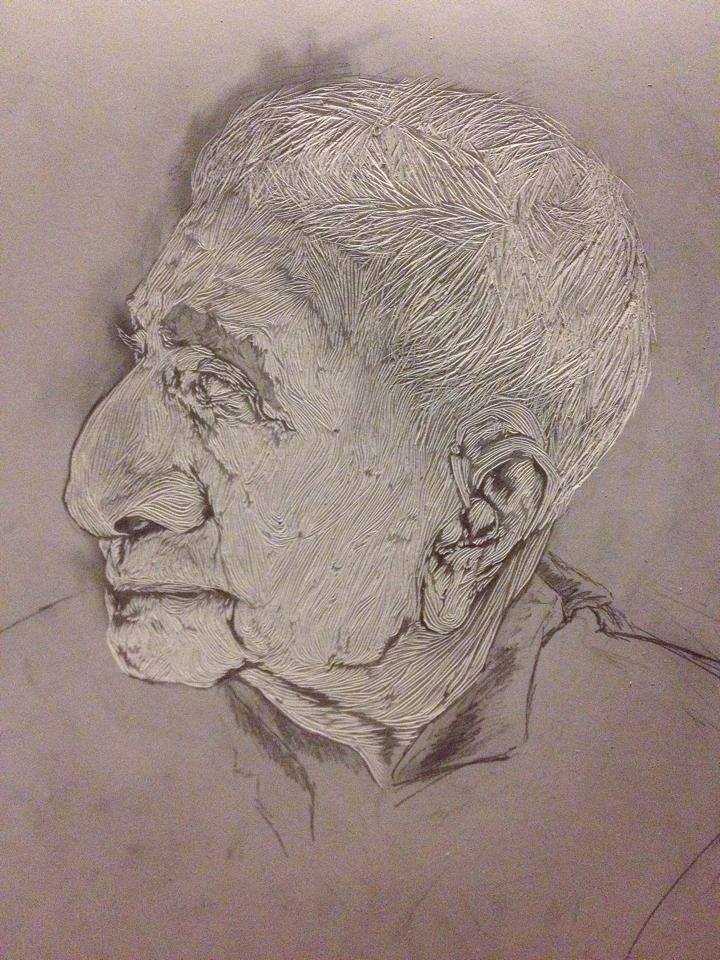

One particularly evocative work features an ancient man with glacial furrows across his foreheads, deep creases around his eyes, a long, hoary beard and gnarled bony fingers wrapped around a bone tobacco pipe.

He could be 75, maybe even 100. He might be from the Siberian tundra or maybe rural France. He might have been a sailor, then again perhaps a hard-bitten prisoner from the gulags. He might be from the 19th century. Don’t ask Zorn, she won’t say.

“All my work is of old males, I really like the texture to their faces,” she says.

“I keep them expressionless but there’s often a mood, other elements, you can read into it.

“I play with different backgrounds, different cultures, like Indian or Russian, where I can convey something without emotion.

“Races have rather distinct appearances and I think that’s just again something each viewer can read into it what they think of the subject’s different background and culture. They might look and see different emotions.”

If artists jealously seek out their own place and style, their own oeuvre, Zorn’s anything about prescriptive in her appreciation of other art or practitioners. She’s intrigued by the ability of some tattoo artists, for instance; their line, accuracy and sense of proportion and balance.

Zorn sports four or five small tattoos herself, and one larger exhibit across her back – a black and white Picasso painting of his second wife Jacqueline. It’s about as different to her own work as you could get.

But that same generosity of artistic spirit extends to Zorn’s portfolio. She might restrict her work to linocuts and her subjects might be enriched by anonymity and mute expression, but the works themselves vary in texture, in cut, in detail and in starkness.

Some faces leap off the print, almost striking the viewer; others are more subtle, inviting an audience, insinuating themselves into the viewer’s perception.

Zorn has been accepted into this year’s Glen Eira Gallery Silk Cut Award – one of the richest print awards in Australia – and it’s fair to say she’s excited.

“I’m feeling pretty good about it,” she says, proudly.

“The work I’m submitting is called Man 5. It is the biggest work I’ve done, 60.5 x 64.5 cm. It’s interesting, too, he’s my friend’s grandfather. She emailed me an image – I haven’t met him in person.”

Maybe that’s the trick for this artist. Keeping a distance from her subject. Letting their face do the talking.

After all, maybe it really is like George Orwell once put it: “At 50, everyone has the face he deserves.”

LINK: www.facebook.com/Keren.Zorn?ref_type=bookmark