by NOEL MURPHY

CHRISTMAS DAY, 1856: “Started about 7.30 for Apollo Bay – crossed the Barwon twice near its source, rode about five miles through an undulating country well watered and plentifully sprinkled with wild cattle.

“ … at last found ourselves in a rack cut through a dense forest only wide enough for one horse to pass at a time … the trees were magnificent, hundreds of them being at least 400 feet high and 20 feet in diameter at the base running up as straight as if turned by a lathe and without a branch until near the top.

“ … The last hill was a teaser and went by the name of Burst-my-gall. We arrived at the beach about sunset, had a glass of grog in Robertson’s tents and then went to Brodie’s hut where we kept up Christmas by singing and drinking until 12 o’clock when we turned in thoroughly tired.”

……………

KEEPING tabs on the workers was hard work in the mid-1800s but someone had to do it and in this case Edward Snell was just the man.

His Yuletide thrashing through the Otways and beachside carousing was driven by the need to find out why sleepers for his new Geelong-Melbourne railway line were less than the desired quality.

Turned out the 90 men employed by The Apollo Bay Company were slackers and as Snell reported: “All seemed to do pretty much as they thought proper – in fact the company were regularly going to devil for want of proper management.”

Snell subsequently presided over the loading of sleepers on to the brig Christina and made his way back to Geelong, although not without before escaping the ship in heavy weather that later drove her ashore.

Goes with the turf, just grist to the mill … however you care to term it, it was all in a day’s work for the remarkable Snell _ a young man who by turns played the role of architect, engineer, artist, surveyor, planner, draftsman, businessman and key figure in Geelong during the roaring Gold Rush days.

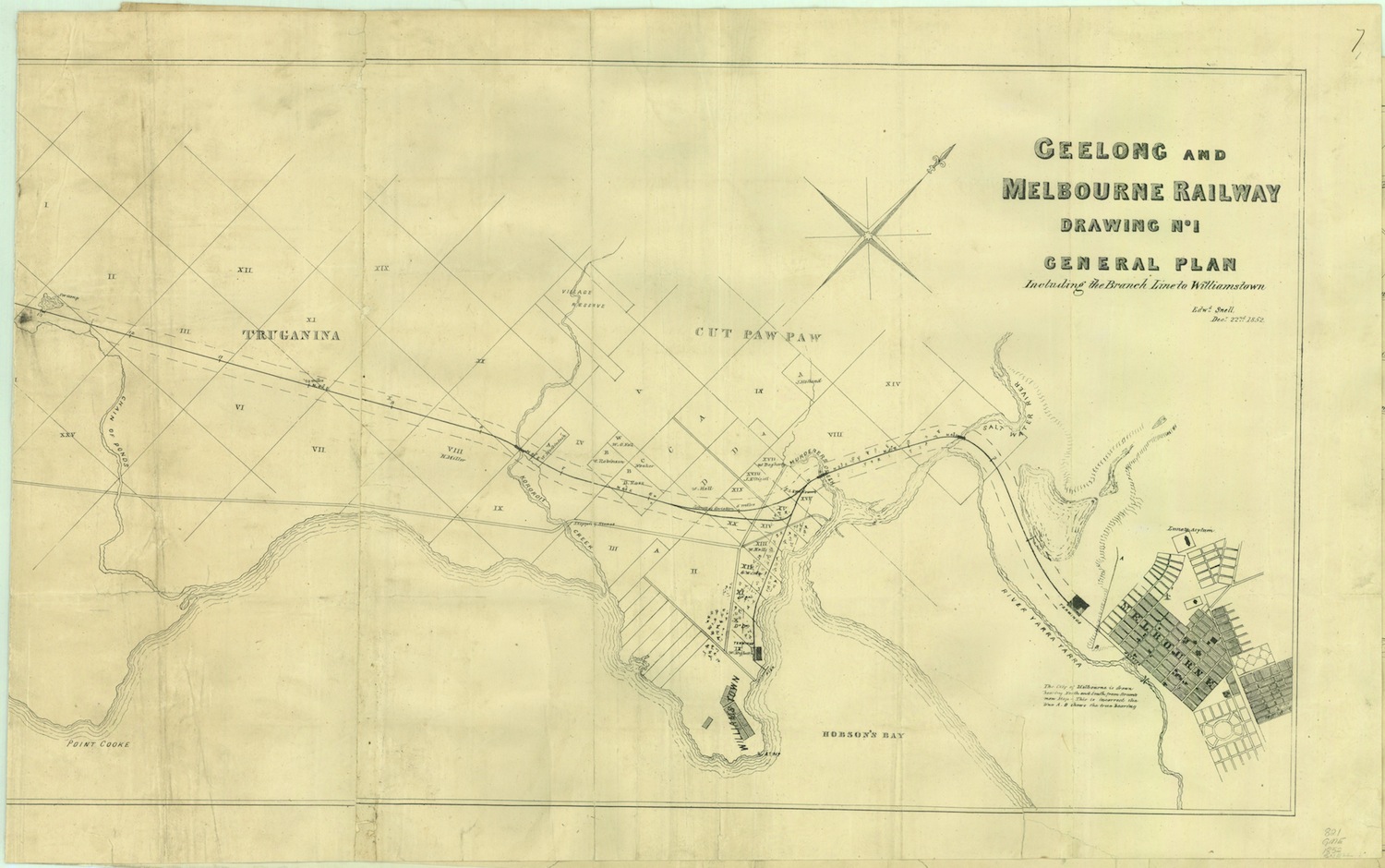

Snell is best-known, and with some notoriety, for building the railway line to Melbourne. The notoriety came from the fact the official opening was a disaster. The train’s locomotive engineer Henry Walter was killed after belting his head on a bridge at Cowie’s Creek while waving to the crowd.

Snell was accused of scrimping on materials and spending, the bridge should not have been so close to the train, but he argued otherwise, and vehemently. The government of the day had thrown up every obstacle possible, he argued, and demanded “a sufficiently durable line at moderate cost … and with all possible economy”.

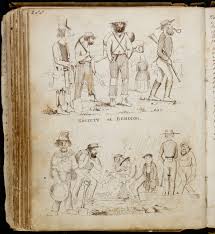

Nasty business, really, but Snell was never one to stand on ceremony or look the other way from a challenge. Today, he’d been viewed as patently politically incorrect. He painted faces on the bloated bellies of malnourished Aboriginal kids, sketched naked Aboriginal women in their splendour, slaughtered caterwauling moggies with a sword through the roof of his hut, made a mess of himself on drinking sprees … in general, had a wild time in the Antipodes where it was his unabashed intention to make his fortune before heading home to the Old Dart.

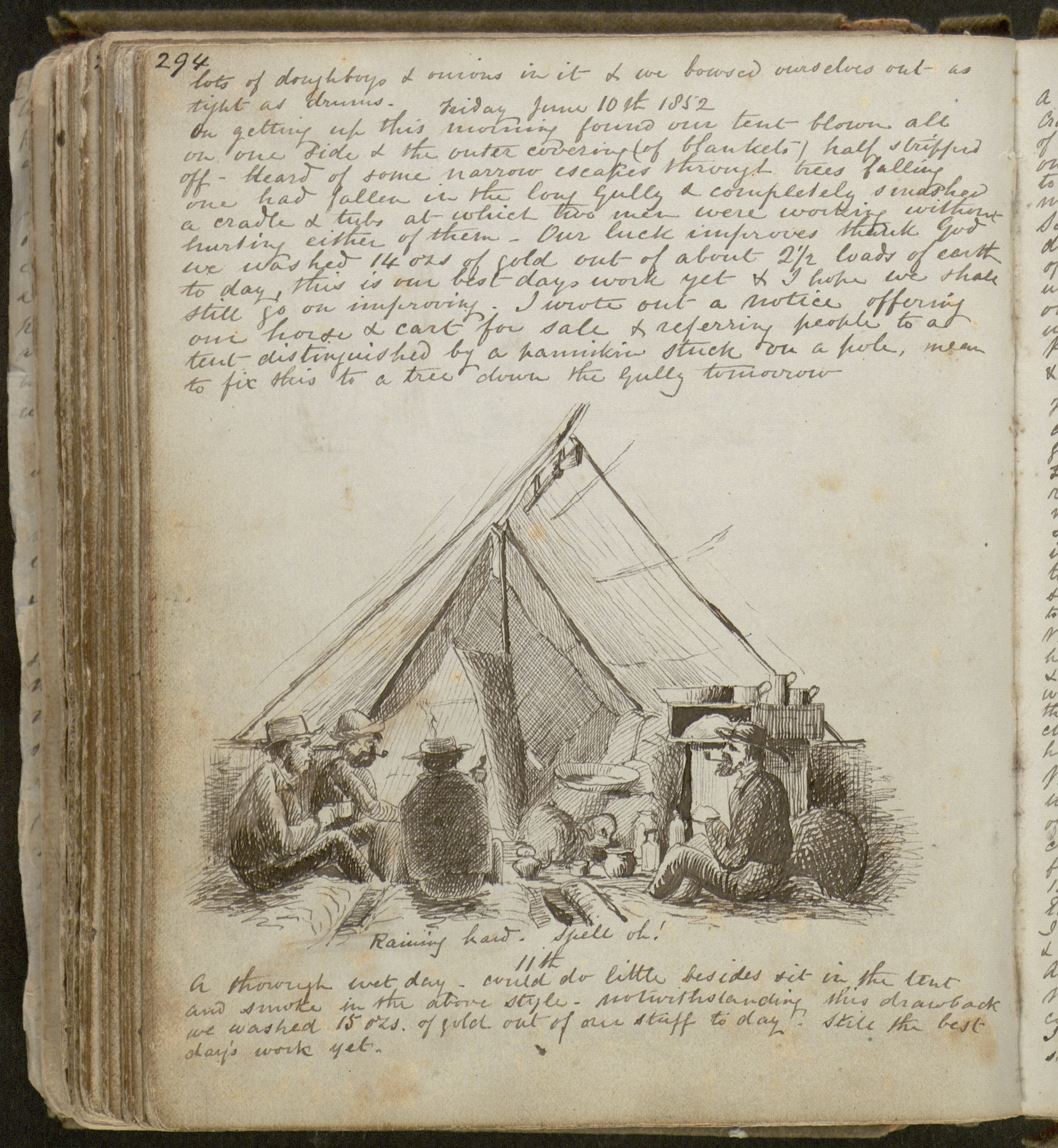

Snell was a conscientious diary-keeper, for the main part anyway, and maintained accounts, sketches, caricatures and watercolours providing a wicked insight to colonial life in Geelong, Adelaide, the Yorke Peninsula, Tasmania, the Murray and the goldfields.

Snell had been deeply involved, as an engineer, in the mid-1840s railways boom of Britain and used his experience and credentials to full effect in Victoria, while using his new-found power as leverage in Britain for professional and material assistance.

Working with German-born Ferdinand Kawerau, Snell also ran a lucrative architect and surveyor business; “trade flourishing to no end” and “making lots of money”, as he voiced it. But the boom driving this success, like the popularity of his single-line to Melbourne with its culverts, bridges, fencing, crossing and signals all found wanting, was relatively short-lived.

His talents across numerous fields, however, plus his income from the railways contract, kept him more than afloat – he’d also profited handsomely on the goldfields. Snell’s reputation, however, was suffering by degrees and in 1858 he cleared out for old England, where he was able to retire comfortably.

His diaries, resident with the State Library of Victoria, are a vibrant, leap-off-the-page account of an exuberant, rambunctious period of history coloured by shooting expeditions, bush rambles, encounters with snakes and whaling stations, bush camps, life at sea, singing and boozing, trapping, exploring, fishing, yabbying, sketching, prospecting, fisticuffs, chasing runaway horses, leaky boats and steamers, bushranger court trails, mud and rain, circuses, chess, pubs, damper, miners and more.

The diaries are peppered with cartoons, caricatures, sketches and more elaborate artworks: serpents, wasps, lizards, hotel breakfast scenes, rain-sodden diggings fiascos, tent life, mountains, coasts, lakes, rivers, mechanical diagrams, horse-riding, all manner of people, ships, whales, grave sites …

Snell catalogued various scenes of early Geelong — Corio Bay, the Barwon Heads bluff, Buckley Falls, the lighthouse at the Port Phillip Heads, his own house on Skene Street – which still stands today – boating on Corio Bay, Geelong township, the Johnstone Park swamp, his railway station terminus.

Few people resident in Lara’s Archimedes Avenue, or Brunel Close, or Watt Street, probably realise it was Snell who designed their original subdivision, naming it after Swindon, where he’d honed his railways craft with the Great Western Railway company a decade earlier before coming to Australia.

Other names he used for the township included Stephenson, Smeaton, Nasmyth and Rennie – all illustrious engineers – but the subdivision, while approved, didn’t come into being for another century or so.

One of this scribbler’s favourite entries in Snell’s diaries dates to January 21, 1851, when one of his mates surfaced after a bender:

“At day break this morning Mackay returned having been missing since the night of the 19th. I let him in – he had neither hat nor shirt on, his coat was in tatters and he was nearly stung to death by mosquitoes.

“He had been in some salt water with his clothes on and his watch was spoiled, he had also been in ‘chokey’ and been fined by a magistrate for being drunk, and he had a bill to pay for damage done during his spree – he had no very distinct recollection of what had occurred but he had had a glorious spree and no doubt felt great satisfaction in reflecting thereon.

“At dinner time a neighbour of ours named Jones came in, he has lately had some money left him and had been on the spree with Mackay.

“They had been eating bank notes and smashing bottles and glasses at various public houses and Jones’ recital of damage he had done at the Norwood Arms started Mackay off again. He did not return till 3 in the morning and was as drunk as ever.”

Scoffing down money … now that’s your roaring days for you.