One person goes missing in Australia every 18 minutes. While most of them are later found, approximately 2600 people remain lost. Their families and loved ones remain tormented by so many haunting questions and rarely receive any resolutions. Fatima Halloum speaks to the director of an organisation whose mission is to raise awareness for those who haven’t been found.

Families of missing people are thrust into an unimaginable situation.

It’s a stark and frightening reality that Leave a Light On director Suzie Ratcliffe knows all too well.

“You read about it happening in the paper, or you see it on the news, or on social media, and you think, poor family or I really feel for them. But then you turn the page and move on to your next story.”

Suzie lives in Victoria, but works with people all across the country.

Through her organisation, she provides emotional support for the families of missing people and promotes cases that are desperate for public assistance on her Facebook page.

“The concept for Leave a Light On was initially created because for families of missing loved ones, one of their greatest fears is that they’ll be forgotten.

“We’re reliant on somebody remembering a vital piece of information if we’ve got any hope of finding our loved one, or if it was a crime, then bringing someone to justice.”

Because there are so many cases that people never hear about, Suzie is hopeful that at the very least, she is able to generate national awareness.

“Just a small piece of information that we put on our page encourages people to go forth and do a bit more research. And then they suddenly realise that, ‘oh I was in that area’, or ‘I used to live in that suburb’ or they might know someone that could have been in that area,” Suzie said.

“It is always important to speak about it with other people. Because that person might not realise that they have that little piece of information that’s needed by the police to be able to link it all together.”

Suzie says it never feels any less heart-breaking reading the stories of missing people, researching their cases and connecting with their families, but they draw strength from each other.

“They feel like my own family. Every time they have disappointing news or a disappointing outcome, or they have good news, or they’re contacted by police I feel the elation, I feel the emotions.”

“It’s a horrible connection to be dealt with. I wish I’d met a lot of these families under completely different circumstances.

But unfortunately, we’ve all been drawn together by the same type of situation.”

Suzie knows first-hand what the families she connects with are going through.

In 1973, in Adelaide, South Australia, her sister Joanne went missing. Her disappearance occurred only seven years and 13 kilometres from the beach where the Beaumont Children vanished.

“I never thought we would be in the same position as them,” Suzie said.

“Fast forward, and suddenly it’s our family that’s in the newspaper, and it’s our family being spoken about on the radio, and we’re the ones that are putting ourselves out there and trying to get people to come forward with information.”

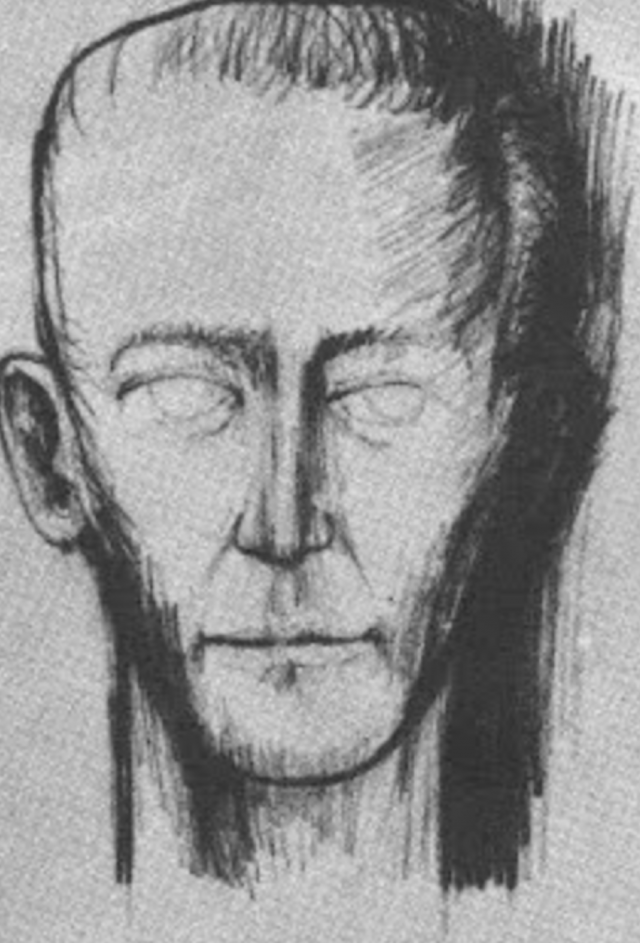

Suzie’s family, her mum, her dad, her older brother and her sister Joanne were attending a football game, seated beside them were strangers, four-year-old Kirste Gordon and her grandparents.

When Kirste needed to use the bathroom, Joanne offered to take her and the two went together to the toilets.

It’s been 48 years, six months and 19 days since Joanne and Kirste were last seen.

Spectators remember seeing Kirste in the arms of a man, 11-year-old Joanne followed, looking distressed.

Despite numerous suspects, police were unable to locate the girls and Suzie’s father, mother and brother died without knowing what happened to Joanne.

“When you lose someone through death, they’ve got a grave, you can go and visit, you can bury them. You can begin the grieving process and with that grieving process comes a healing process as well,” Suzie said.

“But with not knowing what happened to your loved one, they’re out there somewhere, whether they’re deceased, or whether they’ve been held captive, or are horrible victims of crime, or they’ve gone missing through adventure, you’re constantly wondering where they are.”

Suzie’s parents would leave their front porch light on, in the hopes that if Joanne returned, she would know they were waiting for her.

Missing person’s cases are often limited by state lines and Suzie aims to give the cases she advocates for national coverage, not just local publicity.

“Missing persons don’t know any borders,” Suzie said.

“We don’t just stick to our little suburbs. I travel 40 minutes to work. I can hear about things that happen on the other side of Melbourne, I travel up to Wangaratta every second week. I can see things up there but not necessarily know that I might have seen or heard something that’s important.

“Ultimately, someone somewhere knows something about our missing persons. And if we can reach that person, then all the better to be able to encourage them to come forward and contact Crime Stoppers or contact the police or family in the hope that information they have can help.”