Psychiatrist and new Bellarine Peninsula local Christos Pantelis first took up photography on a trip to Greece in 1975 and has “not put the camera down since”.

He finds himself in the lens as he takes Luke Voogt behind the Iron Curtain for a glimpse into life in 1980s Soviet Russia.

Almost half a century since Christos Pantelis took up photography “seriously”, his snap of a monastery perched atop the cliffs in Meteora, Greece, remains one of his most prized.

“I was at the end of my second year of medical school at the University of Melbourne, in 1975,” the Bellarine Peninsula psychiatrist remembered.

“The Greek Club had organised the trip and it was an opportunity to visit my parents’ homeland and meet relatives I had only heard about.

“The monasteries atop the cliffs in Meteora were quite extraordinary. I visited this area again in 1982 but still prefer my photo from that first trip.”

After finishing medical school in 1979 and working as a resident at St Vincent’s Hospital, he took a year off in 1982 to devote himself to photography and exploring the world.

He travelled to Malaysia, before returning to Greece and travelling across Western Europe.

Then, he stepped out of his comfort zone and went behind the Iron Curtain.

Back then Russian president Vladimir Putin was a young KGB agent, the Berlin Wall still divided eastern and western Germany and ABBA was big, even in the USSR, according to Christos.

“It was not usual for westerners to travel to these countries as tourists, especially the USSR,” he said.

He began his journey across the Eastern Bloc by crossing the Greek-Yugoslav border, stopping first at Lake Ohrid, one of Europe’s oldest lakes.

The lake was a favourite holiday destination for other Yugoslavs, but Christos was most fascinated with the locals.

“The hay bearers were astonishing – middle-aged women who carted huge bales of hay on their backs,” he said.

Christos encountered a wedding procession in Ohrid too and photographed the wedding party and the newly-married couple in their home.

Next, he moved onto Hungary, and after leaving Budapest spent a day in Szentendre, on the Danube, capturing the relationship of a local father and son on film.

Then, he entered the USSR, through Ukraine.

“I was able to join an English tourist group a few days after I arrived in Kiev,” he said.

“A visa was required for every city I visited, and I was not to venture outside of those cities.

“We had designated guides who acted as chaperones for the whole trip.

“But I went out of my way to meet local people outside of these groups.

“The people I met were warm and generous, even when they had little. They didn’t have the access to the things we have – there were times I saw queues for ice cream in Kiev and things like that.

“I had the impression it was dangerous for them to get too close to foreigners.

“Obviously the regime was oppressive and people had to be cautious – the KGB was ever-present.

“But they were very interested to get a perspective of outside as well.”

The group then travelled to Uzbekistan, visiting cities along the Silk Road – Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent – which were full of colour, beautiful temples and crowded open marketplaces, he said.

The country neighbours Afghanistan, which the USSR was then at war with.

But their next destination, Moscow, was a stark contrast to the Silk Road cities.

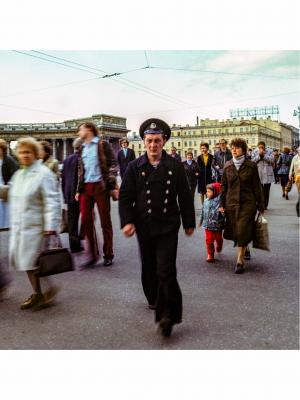

“Moscow was rather grey, sombre, and seemed very serious. The English group left after Moscow, and I travelled to beautiful Leningrad, now St Petersburg.

“There was a feeling of being monitored throughout the trip in the USSR, especially so as we got closer to Moscow and Leningrad.”

Christos took many photos, using two cameras and a tripod, of people going about their daily lives in Leningrad.

“During one of my photography sessions, I was approached by a suspicious-looking man in a trench coat,” he recalled.

“He asked me about my pictures and made small talk.

“He then gave me a small, sealed container – like a sardine can – that could be used to hold coins. I considered this very unusual and worrying.

“I wondered what was inside and if it was somehow a way to monitor my movements. I decided to trust my feelings and dropped the container into a nearby canal.

“A few days later, I was travelling by train to Helsinki with a fellow traveller, an older American tourist.

“On the border with Finland, I was taken off the train and questioned as my belongings were examined.

“My fellow traveller was wondering how to contact my family, should I not return.

“I had 80 roles of exposed film and I thought I was going to lose it all, but they left it alone, so I assume they weren’t too worried about it.

“That suggested they knew what I was photographing. Were they looking for that container?”

After two and a half weeks in the USSR, he crossed into neutral territory.

“I recall being so pleased to see the smiling faces of the Finnish border police and seeing fresh oranges and healthy-looking cows,” he said.

But his weeks behind the Iron Curtain shaped his outlook on how people coped in difficult circumstances.

“It was a lesson in humanity, adversity and the resilience of the human spirit that I have carried forward in my professional life as a psychiatrist,” he said.

Christos travelled through Scandinavia and Western Europe, before returning to Greece, and a subject that inspired his early photography.

He and a lawyer from Athens visited the breathtaking monasteries of Mount Athos, an intriguing autonomous region where hermit monks isolated themselves from society.

“Access was by boat and foot,” he said.

“We arrived at each monastery before sunset, at which time the gates would be locked and the monks would retire before early mass at 2am or so.

“We would join early mass, followed by breakfast at daybreak.

“The monasteries were austere institutions, which had not changed greatly since they were built. They used to house hundreds but their numbers had gradually dwindled to around 50 or less.”

He also photographed nearby monastic hamlets, where villagers lived alone or in small dwellings and worked on handicrafts.

He moved to London in 1983, where he worked as a psychiatrist and researcher for almost a decade.

His beloved aunt Paraskevi, who had schizophrenia, inspired him to pursue that field.

Paraskevi followed Christos’s parents migrating to Australia from Greece in 1955, the year he was born.

“She was warm, engaging, quite humorous, and was always spoiling us,” he said.

“She was quite important in my life and actually coped pretty well, and was well-liked in the community.

“However, the symptoms of her schizophrenia would torment her, and at times caused her and those around her a great deal of grief.”

He continued to study schizophrenia in Australia, and conducted world-leading research using imaging to map brain changes in young people developing the disorder and other conditions.

In 2004, he and fellow professor Dennis Velakoulis established the Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre, and Christos continues to work with schizophrenic patients, often online amid COVID-19.

He has continued to pursue photography, especially on the Bellarine Peninsula, which he and his wife visited regularly since returning to Australia in 1992.

They moved to the peninsula in May 2020, and during the pandemic Christos has set out to capture seascapes at twilight and daybreak in his new coastal backyard.

Christos recently digitised many of his early pictures taken on Kodachrome slides and is exhibiting them, most for the first time, at Focal Point Darkroom and Gallery in North Geelong.

The gallery’s Members Exhibition reopened on Wednesday following the easing of lockdown, and features photographers from across Geelong including Christos’s daughter Zoe.

“She’s taken up my old film cameras and we’re taking photos together down here,” Christos said.

“She’s quite talented actually – she’s got an interesting perspective.”

For Christos the exhibition is yet another show of human resilience, both by local photographers and gallery owner Craig Watson, who recently renewed the lease for the business despite the pandemic’s devastating impact.

“I think we need to deal with adversities that we’re confronted with, and it’s great when we move forward in a creative and positive way,” he said.

“I’m grateful to Craig for his enthusiasm and perseverance, especially over the last 18 months during such difficult times.”

Details: focalpointdarkroomgallery.com.au